| | | Dylan dans la presse |  |

|

+31Mathphil Sherpa Monsieur Plume Skeleton Keys LouisTheKing Chinaski ECHO49 Delia_2 odradek Moonwatcher dr.out Diamonds&Rust gengis_khan Jack Fate Esther Soledad vox populi Aleyster Moonlight used_spoon JeffreyLeePierre Simmm David Desmos Sardequin John Wesley Harding Baptiste hazel Oyster No fun gepetto 35 participants | |

| Auteur | Message |

|---|

gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 14 Juil - 20:17 Mar 14 Juil - 20:17 | |

| - hazel a écrit:

- Un bon papier de Ouest France sur le concert de Poupet :

http://www.larochesuryon.maville.com/actu/actudet_-poupet-2015-pourquoi-on-a-deteste-aimer-le-concert-de-bob-dylan_une-2799663_actu.Htm Oui j'allais le publier également ! un bon article qui remet les choses à plat. Et le journaliste a quand même réussi à faire une photo du concert !  On saura au moins que Bob a aimé l'endroit ! | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 14 Juil - 20:23 Mar 14 Juil - 20:23 | |

| et bien les journalistes de Poupet sont des rebelles ! il y a des photos du concert :

http://www.festival-poupet.com/gallery/1307-bob-dylan

bien classieuse en plus

| |

|   | | used_spoon

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2167

Age : 33

Date d'inscription : 19/12/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 14 Juil - 22:38 Mar 14 Juil - 22:38 | |

| Bob Dylan - Festival de Poupet 2015 : https://youtu.be/VkRSJr_q-1U

Et même un extrait vidéo ! | |

|   | | Jack Fate

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 1010

Age : 43

Date d'inscription : 21/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mer 15 Juil - 1:52 Mer 15 Juil - 1:52 | |

| Un autre article, sur Albi cette fois

http://www.la-croix.com/Culture/Musique/A-Albi-Bob-Dylan-au-crepuscule-2015-07-13-1334187 | |

|   | | Chinaski

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 444

Localisation : Trans City

Date d'inscription : 14/07/2006

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mer 14 Oct - 21:12 Mer 14 Oct - 21:12 | |

| http://www.telerama.fr/musique/bob-dylan-en-1965-j-y-etais-par-louis-skorecki,132526.php | |

|   | | gepetto

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 338

Localisation : at the seine's edge

Date d'inscription : 23/01/2008

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Dim 18 Oct - 17:30 Dim 18 Oct - 17:30 | |

| Un bon papier dans Le Figaro hier (avec photo) et rien dans Libé !

Comme dit l'autre : "Les Temps Changent" | |

|   | | JeffreyLeePierre

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2899

Age : 57

Localisation : Paris

Date d'inscription : 06/01/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Dim 18 Oct - 20:46 Dim 18 Oct - 20:46 | |

| Sinon, y a aussi eu hier un bon 5 minutes en fin de JT de la 2ème (en attendant la dérouillée du soir).

Avec une interview de 25 secondes de Freddy Koella quand même. Presque pointu, donc.

Mais rien sur la nouvelle tendance de la set-list sinatrienne. Moralité : le couillon qui se décide sur la foi de ce reportage encore très orienté "ex-porte parole de sa génération" sera probablement fort déçu... | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mer 28 Oct - 6:58 Mer 28 Oct - 6:58 | |

| Je viens de mettre la main sur la video dont tu parles. 5 minutes de Dylan dans un JT NATIONAL pas pour dire qu'il est mort, c'est une sacré surprise quand meme! Et Freddy en interview...! J'aurais préféré 5 minutes de Koela qui parle de Dylan mais la cest utopiste. On a meme le droit a un petit extrait du grandissime "it take a lot to laught" de 2003 capturé via youtube! Cest con mais ca m'a fait sourire parce que cette version est une sacré decharge electrique!

Merci pour l'info! | |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 2 Nov - 1:57 Lun 2 Nov - 1:57 | |

| Un article parfois amusant de l’Atlantic Review, qui donne des aperçus sur le Dylan de proximité — si vous voyez ce que je veux dire (en fait je cherchais une expression moins ironique, mais je n’ai pas trouvé).

JAN 23, 2014 @ 2:00 AM

Seven Questions for Bob Dylan

He has given countless interviews, cowritten a movie about himself and authored an autobiography, released 35 albums, and toured for half a century. So why do we know nothing about this man?>> PLUS: A RE-TELLING OF DYLAN'S 2009 RUN-IN WITH THE COPS, TOLD BY THE COP

BY TOM JUNOD

Fame Pictures; historic Dylan photos: AP

Published in the February 2014 issue

How do you like your eggs, Bob Dylan, How do you like your eggs? You're walking on broken legs, Bob Dylan, But you still make us beg, Bob Dylan. So how do you like your eggs?*

You can't look at him. If you work at one of the arenas where he plays, you're not allowed to look at him when he makes his way from the bus to the stage. If you play at one of the arenas where he plays—if, like Wilco's Jeff Tweedy, you're a fellow musician, sharing a bill—then you have a decision to make, occasioned by the privilege and problem of proximity. You'll be standing around and suddenly there he'll be, and you have to figure out if you're allowed—if you allow yourself—to behold Bob Dylan.

* We asked Mr. Dylan's representatives what he eats for breakfast. Their response: "Next question."

Tweedy didn't think he was when he was traveling last summer on Dylan's Americanarama tour. "First or second show of the tour, I was standing out in the middle of the dressing-room area—you know, a bunch of trailers in a U-shape. The show was about to start for Dylan, and he came through with his dressed-to-the-nines gang. He saw me, and I figured I was just supposed to avert my eyes, because I didn't think I was supposed to be where I was, standing in the way."

Tweedy was about to stare at the ground when he heard Dylan say, "Hey, Jeff, how's it going, man?"

That's all he said and all he had to say. "It was the biggest thrill of my life," Tweedy says. "I was like, I hope people saw that—that it was real."

How do you sleep at night, Bob Dylan, How do you sleep at night? The morning sun's so bright, Bob Dylan, Your band is still so tight, Bob Dylan. So how do you sleep at night?**

Bob Dylan is either the most public private man in the world or the most private public one. He has a reputation for being silent and reclusive; he is neither. He has been giving interviews—albeit contentious ones—for as long as he's been making music, and he's been making music for more than fifty years. He's seventy-two years old. He's written one volume of an autobiography and is under contract to write two more. He's hosted his own radio show. He exhibits his paintings and his sculpture in galleries and museums around the world. Ten years ago, he cowrote and starred in a movie, Masked and Anonymous, that was about his own masked anonymity. He is reportedly working on another studio recording, his thirty-sixth, and year after year and night after night he still gets on stage to sing songs unequaled in both their candor and circumspection. Though famous as a man who won't talk, Dylan is and always has been a man who won't shut up.

** We asked Mr. Dylan's management about Dylan's sleeping habits. The response: "Next question."

And yet he has not given in; he has preserved his mystery as assiduously as he has curated his myth, and even after a lifetime of compulsive disclosure he stands apart not just from his audience but also from those who know and love him. He is his own inner circle, a spotlit Salinger who has remained singular and inviolate while at the same time remaining in plain sight.

It's quite a trick. Dylan's public career began at the dawn of the age of total disclosure and has continued into the dawn of the age of total surveillance; he has ended up protecting his privacy at a time when privacy itself is up for grabs. But his claim to privacy is compelling precisely because it's no less enigmatic and paradoxical than any other claim he's made over the years. Yes, it's important to him—"of the utmost importance, of paramount importance," says his friend Ronee Blakley, the Nashville star who sang with Dylan on his Rolling Thunder tour. And yes, the importance of his privacy is the one lesson he has deigned to teach, to the extent that his friends Robbie Robertson and T Bone Burnett have absorbed it into their own lives. "They both have learned from him," says Jonathan Taplin, who was the Band's road manager and is now a professor at the University of Southern California. "They've learned how to keep private, and they lead very private lives. That's the school of Bob Dylan—the smart guys who work with him learn from him. Robbie's very private. And T Bone is so private, he changes his e-mail address every three or four weeks."

How does Dylan do it? How does he impress upon those around him the need to protect his privacy? He doesn't. They just do. That's what makes his privacy Dylanesque. It's not simply a matter of Dylan being private; it's a matter of Dylan's privacy being private—of his manager saying, when you call, "Oh, you're the guy writing about Bob Dylan's privacy. How can I not help you?"

Hey, do you eat meat, Bob Dylan, Will you eat some meat? You're on the Mercy Seat, Bob Dylan. You're selling "The Complete Bob Dylan," Pledged to your own defeat, Bob Dylan, So will you eat some meat?***

It's because of us, of course—because of us that he practices privacy as an art, because of us that he abjures politics, because of us that he retreats from us, because of us that he no longer talks to us from the stage. "What the hell is there to say?" he has asked, adding that no matter what he says, we would want him to say more. We would want him to lead us. We would want him to tell us the meanings of his songs. We would want him to play his songs the same way every night, the same way he played them on his records. We would want him to join our causes. We would want him to deliver prophecies. We would want him to tell us about his family, and if he didn't answer, we'd reserve the right to go through his garbage cans.

*** We asked if Dylan is a vegetarian. The response: "Next question."

"I've always been appalled by people who come up to celebrities while they're eating," says Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer who has taken pictures of Dylan, Springsteen, and just about every other god of the rock era. "But with Dylan, it's at an entirely different level. With everybody else, it's 'We love you, we love your work.' With Dylan, it's 'How does it feel to be God?' It's 'I named my firstborn after you.' In some ways, the life he lives is not the life he's chosen. In some ways, the life he leads has been forced upon him because of the way the public looks upon him to be."

That's the narrative, anyway—Dylan as eternal victim, Dylan as the measure of our sins. There is another narrative, however, and it's that Dylan is not just the first and greatest intentional rock 'n' roll poet. He's also the first great rock 'n' roll asshole. The poet expanded the notion of what it was possible for a song to express; the asshole shrunk the notion of what it was possible for the audience to express in response to a song. The poet expanded what it meant to be human; the asshole noted every human failing, keeping a ledger of debts never to be forgotten or forgiven. As surely as he rewrote the songbook, Dylan rewrote the relationship between performer and audience; his signature is what separates him from all his presumed peers in the rock business and all those who have followed his example. "I never was a performer who wanted to be one of them, part of the crowd," he said, and in that sentence surely lies one of his most enduring achievements: the transformation of the crowd into an all-consuming but utterly unknowing them.

"We played with McCartney at Bonnaroo, and the thing about McCartney is that he wants to be loved so much," Jeff Tweedy says. "He has so much energy, he gives and gives and gives, he plays three hours, and he plays every song you want to hear. Dylan has zero fucks to give about that. And it's truly inspiring. The joke on our tour was that his T-shirt should say PISSING PEOPLE OFF SINCE 1962. If you dropped people out of a vacuum from another planet and planted them in a field somewhere so that they could study us, and there's a guy half-decipherably singing jump-blues songs almost in the dark, and there's people watching him—well, it wouldn't make any sense… ."

It makes sense only in the terms that Dylan has established for himself: His life and his art have combined to create the oral and written parts of a continual test that most of us fail. The only way to pass is to go to the shows, for as Dylan told Rolling Stone a few years ago, "The only fans I know I have are the people who I'm looking at when I play night after night." He's notorious for creative disruption—for rendering the old chestnuts unrecognizable—but as he's gotten older, so have his fans, and the test has grown more rigorous still. He's not only "chosen not to deliver the set that his old fans would like to hear," as one of his longtime promoters, John Scher, says. "He's chosen to play in a stand-up situation, which is not a situation that his older fans enjoy." That is, when booking his tour, his agent prefers that the shows are to be general admission, with no seating. That is, he makes the geezers stand, as if to say, in Scher's words, "If you can't stand up, you shouldn't be there."

It is not that Dylan is necessarily more private than McCartney or Van Morrison or Neil Young or Bono—we know as little of their lives as we do of his. It is that Dylan has perfected the dynamic that makes his privacy simultaneously possible and intolerable: The poet needs the asshole. The asshole needs the audience. And when you go to a Dylan show, both the poet and the asshole have you right where they want you.

How do you get your mail Bob Dylan, How do you get your mail? You've put yourself in jail, Bob Dylan, Are you still chasing tail, Bob Dylan? That's been your third rail, Bob Dylan, So how do you get your mail?****

Here is a Dylan story, featuring neither poet nor asshole. Tweedy heard it from his bass player. His bass player heard it from a girl he knows. The girl lived it. She was walking down the street in Memphis, Tweedy thinks it was. "She looked into the basement windows of a hotel, and she saw Bob Dylan swimming in the pool with his bodyguard. She decided, 'Let's go see what happens if I say hi.' She walked into this hotel, and she walked over to the pool and said hi, and he took pictures with her. She said that she was a big fan and he said, 'How many times have you come to see me?' She said, 'Twenty-five.' And he said, 'Oh, man, how can you take it?' "

**** We asked if Dylan uses e-mail. His representatives would only say that he might. Or might not.

There are a lot of stories like this—Dylan with the carapace of celebrity removed; Dylan like a girl, pretty and lonely, finally asked out by a suitor uncowed; Dylan the shy midwesterner; Dylan taking extra time to sign autographs, hesitating

only when someone asks him to sign vintage vinyl, because he knows he's being used; Dylan posing with the daughter of a father who's waited by the wings of the stage; Dylan dutifully and graciously going about the business of fame; Dylan gratified to be finally treated as another human being. There are enough of these stories to prompt the question: Is being treated as just another human being all that Dylan wants?

The answer is probably no, for Dylan is also known for staring straight ahead, stone-faced as a judge, when people approach him, until they go away.

And what makes Bob Dylan stories interesting is that the only person who can decide their outcome is Bob Dylan, so you never know how they're going to go. For instance, last summer Wilco and My Morning Jacket went on tour with him. Both were led to believe that they'd be playing with him, but only Jim James of My Morning Jacket expected to hang out with him and, like, jam. The result, though predictable, played out like a metaphor for the vagaries of salvation: Jim James, with his expectations, had his expectations dashed; Jeff Tweedy, with his resignation, came home with stories to tell, such as the time, waiting in the wings, when Tweedy told Dylan that Mavis Staples said hello. Tweedy had produced Staples; Dylan had been friends with her since the Greenwich Village days, so he responded with one of those utterances he specializes in, gnomic and innocent, with the same surprising spin as the lines of his songs:

"Man, tell Mavis she should have married me!"

The question of who Dylan will or won't speak to is one of the animating questions of his public life; and neither friendship nor eminence have anything to do with the answer. He is rumored not to have spoken to his pal Willie Nelson on a recent tour, and Ron Delsener, who's been promoting Dylan for decades, says that when he arranged a Dylan–Van Morrison tour through the UK in 1998, he eventually had to approach Dylan's road manager with a plea: "He's got to talk to Van." Hell, when Dylan accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama, he wore shades and barely stuck around for the postceremony reception.

There is not a person in the world who is not at his feet, and that his humanity exists as the last beating heart inside the last inner circle of celebrity is what makes his humanity perishable and perhaps beside the point. It's the question people have been asking for centuries: How human does the king want to be? More specifically, how human does the king permit himself to be? It's not hard to find out: All you have to do is ask him the same questions you'd ask any other human being, and you'll get your answers soon enough.

How do you do the deed, Bob Dylan, How do you do the deed? You're a walking centipede, Bob Dylan, Oblivious to need, Bob Dylan. You're as old as Harry Reid, Bob Dylan! So how do you do the deed?*****

What do we want from Bob Dylan that he hasn't given us already? The answer is axiomatic: We want that which he won't give. "The list of stupid questions you can ask Bob Dylan is endless," says John Scher, and, of course, the most stupid is the one question he has never answered: How does he live? The things we can find out about almost anyone in the world, including the president, are precisely the things we can't find out about Dylan. Does Dylan use e-mail? Does he have a smartphone? Does he eat meat? Does he sleep through the night? Is he kind? "Oh, my God, this is Bob Dylan you're talking about," says someone who knows him well. "How can you ask these questions?"

***** We declined to ask about Dylan's romantic life.

So this is what we know about how he lives. He has homes all over the world, one of which, a manor he owns with his brother in Scotland, is for rent. He lives primarily in Malibu, on a promontory leaning into the Pacific called Point Dume. He has a lot of land surrounded by a corrugated-metal fence, with a horse ring for relaxation and a guardhouse for vigilance. There are junked cars and large commercial shipping containers parked out front as a sort of intentional eyesore, an impediment to prying eyes. He has six children and ten grandchildren, and is said to be very proud of them. He's in shape; he likes to swim and box when he's on the road, and so do members of his band. He's a dog guy. He wears hooded sweatshirts and either combat boots or running shoes. He wore a wig for Masked and Anonymous and kept wearing it when filming was over, at least for a time. Though there are rarely any Dylan sightings, he is not unreachable. When Ron Maxwell, the director of Gods and Generals, got it into his head to ask Dylan for an original song, his music coordinator laughed at him. But when he asked, he got a reply from Dylan's management right away, and both Maxwell and his wife wound up listening to "Cross the Green Mountain" with Dylan and his band at a studio in the Valley. "He was there in his New Balance shoes," Maxwell says. "He was a bit shy, I want to say. We said hi and shook hands. When they played the song back, he was looking away. I heard the whole thing, taking notes. At first I was thinking, 'That's a lot of verses.' Then it was finished, and I stood up and he looked at me. I said, 'I really like it.' He said, 'You do? You like it?' I said, 'I more than like it—are you kidding?' And he relaxed and all the band members relaxed. The tension left the room. They let me know they were all fans of [Maxwell's first Civil War movie] Gettysburg and watched it over and over again on the bus."

He spends a lot of time on the bus for a string of engagements dubbed the "Never-Ending Tour" by the press but called a variety of names by Dylan, one of which is the "Why Do You Look at Me So Strangely Tour?" He rides in a star coach; his band rides in a tour bus; they stay on the ground floors of chain motels, where Dylan can smoke; they use the pool; Dylan doesn't eat where members of his or other bands eat; he doesn't use the dressing rooms; he goes surprisingly light on security, but his security detail is bracingly efficient getting him to and from the bus, as his bus driver is bracingly efficient getting him close to the doors.

His life is often portrayed as an allergic reaction to fame; but he is a creature of fame no less than he's a creature of music and art. Ask people who know him for a description of Bob Dylan outside the prerogatives of fame and the obligations of art, and they have to stop and think; there's just not that much left. The best answer came from Arthur Rosato, his production manager in the mid-seventies and early eighties: "He lives his own life, and that's it. You deal with what's in front of you with him and that's it. He's his own person. He has opinions, but he's not opinionated. He's open, but he doesn't broadcast a lot of stuff. I've had issues, and when you confront him, he listens. He's a different kind of person, because you could say whatever you want to him. He's pretty much one-on-one. In group things, he'll slip into the background. No matter who the people are, he's the same, and he's very attentive to them. That's how he gets along."

That's also how he keeps his privacy without having to talk about it. He knows that the people around him are loyal, and they know that if they weren't loyal, they wouldn't be around him. They not only know not to talk; they also wouldn't think of talking. They listen, then issue their gentlemanly demurrals; when a potential source called Dylan headquarters to ask if he should comment for this story, he was not told no, but rather asked, "What do you think you should do?" It's an honor system, left to the participants to uphold, even when the participants are far from the inner circle. "I didn't get any sense of how he lives," Tweedy says, "and the sense I did get … Well, anything that I did learn, I almost feel like I'm betraying him to share."

It's also a system of omertà, enforced by the threat of expulsion. Those who say that Bob Dylan has never ordered them not to speak also say that if they did speak, they would never be able to work for him again. A member of a band that once opened for Dylan recently published a piece recounting how a friend of Dylan's was banished from the tour for revealing that Dylan had caught a cold; in a recent interview, David Hidalgo of Los Lobos fretted that Dylan hadn't called him since Hidalgo had revealed that he had been in the studio with Dylan, working on a new album. Dylan doesn't say anything because he doesn't have to say anything; he communicates his expectations concerning his privacy in the same way that he communicated to Jim James and Jeff Tweedy how he wanted them to come onstage and play the cover of "The Weight," which he played in the final shows of the Americanarama tour. "We played that song in a different key every night," Tweedy says. "It was never in the same key. The tour manager would say, 'It's in A flat tonight.' Or we'd already be out onstage, and we'd talk to Tony Garnier, the bass player, and somehow ask him which key and he'd say, 'A flat.' And that's in front of a lot of people. But Dylan never told us. I think he likes putting himself and his band into a corner, to see if they can play their way out."

What kind of car do you drive, Bob Dylan, What kind of car do you drive? You're good at staying alive, Bob Dylan. But the bee dies in the hive, Bob Dylan. So what kind of car do you drive?******

It sounds lonely being Bob Dylan, because Bob Dylan likes being around other Bob Dylans, and there are not many other Bob Dylans around. He had to become Bob Dylan, after all, and the ceaseless force of that becoming has been what has given life to his music for as long as he's been making it. Who else is like Bob Dylan? Any human being growing old finds himself in a depopulated world, but Dylan's world was depopulated to begin with—he has remarked that when he was growing up, he felt like he'd been born in the wrong place, to "the wrong parents." The people who know him say they like him, and that he laughs and cries like any other man. But they never say that he's like any other man. And so his community is a community of saints: He loved George Harrison; of course he did—George was a Beatle. George stayed in Dylan's house when George went to L. A. to get experimental treatment for his cancer; but then George died. Dylan also loved Jerry Garcia. And when Jerry died, an addict rather than a seer, Dylan went to the funeral and on his way out told Jerry's advisor, John Scher, "That man back there is the only one who knew what it's like to be me."

****** We asked what car Dylan drives. The response: "Next question."

There is nothing about his life that has not been foretold in his songs. He is an old man now; believing, he says, in "a God of time and space," he sings almost exclusively of memory and loss. Oh, sure, he might be singing about the Duquesne whistle in one song and about a woman named Nettie Moore in another, but those are all just MacGuffins—they all just allow him to sing about his own comic persistence and the fulfillment of his own strange fate.

Who's that on the bus, Bob Dylan, Who's that on the bus? It sure ain't one of us, Bob Dylan. You've never had no trust, Bob Dylan. Your sleep never rusts, Bob Dylan. You'll never slake our lusts, Bob Dylan. But who's gonna carve your bust, Bob Dylan, If not one of us?*******

A few years ago, he was picked up by the police in Long Branch, New Jersey, for the crime of walking in the rain, dressed in sweatpants and a hooded sweatshirt, and peering into the window of a home for sale in a dodgy neighborhood. The news was greeted with a lot of predictable headlines—NO DIRECTION HOME, A COMPLETE UNKNOWN, etc. But here's the obvious question, asked by a friend of his: "Do you really think that's the first time that he's done that? He does a lot of walking no one would expect. He'll walk through neighborhoods undetected and talk to people on their front porches. It's the only freedom Bob Dylan has—the freedom to move around mysteriously."

******* This is a rhetorical question.

People say that a lot about Dylan: His privacy is all he has. It's an odd thing to say. It assumes he's powerless and needs to be protected. But Bob Dylan has never been powerless. Even when his songs stood up for the powerless, he was always pioneering new ways to use the power of his fame, of which the two-way mirror of his privacy is the ultimate expression. Yes, it's cool when Ron Delsener says, "I've seen Dylan walk down Seventh Avenue in a cowboy hat and nobody recognize him. I've seen him eat at a diner and nobody come over to him"—it makes you think that Dylan is out among us, invisible now, with no secrets to conceal, and that at any time we might turn around and see him. But we never do; nobody ever does, even where he lives. What a woman who works the tunnel between the buses and the backstage area at an arena outside of Atlanta remembers about Dylan is not that she saw him; what she remembers is "I was not allowed to look at him."

He was, of course, on his way to the stage when he passed her averted eyes—on his way to be looked at and listened to. It sounds like a paradox typical of Bob Dylan, worthy of Bob Dylan, but it's really pretty straightforward as an exercise of star power. The crossed relationship between Bob Dylan and his audience is the most enduring one in all of rock 'n' roll, and it keeps going—and will keep going to the last breath—because from the start he laid down a simple and impossible rule:

We don't go to see Bob Dylan.

Bob Dylan goes to see us. | |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 2 Nov - 2:02 Lun 2 Nov - 2:02 | |

| Je sais ça a l’air désinvolte de communiquer un papier comme ça en anglais sans un mot de traduction, mais ce soir je suis cané, ce qui veut dire que je le serai encore demain qui en plus est un lundi jour abhorré. Au fait, j’espère qu’il n’a pas été publié déjà ici. En tout cas, au survol, je n’ai rien vu. | |

|   | | JeffreyLeePierre

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2899

Age : 57

Localisation : Paris

Date d'inscription : 06/01/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Ven 6 Nov - 19:34 Ven 6 Nov - 19:34 | |

| Non, non, c'est pas désinvolte.

Merci. | |

|   | | JeffreyLeePierre

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2899

Age : 57

Localisation : Paris

Date d'inscription : 06/01/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 1 Déc - 21:15 Mar 1 Déc - 21:15 | |

| Autre papier que j'ai bien aimé, sur Rolling Stone, pour l'anniversaire de Highway 61 Revisited, par Rob Sheffield :

Happy Birthday, 'Highway 61': Dylan's Weirdest, Funniest Album Turns 50

On the enduring mystique of the icon's second 1965 triumph

Happy 50th birthday to Highway 61 Revisited, Bob Dylan's strangest, funniest, most baffling and most perfect album. Released on August 30th, 1965, it arrived just five months after his previous masterpiece, Bringing It All Back Home, but this was a different guy making a different album, a folk rogue embracing the weirdness and spook of electric rock & roll. "The songs on this specific record are not so much songs but rather exercises in tonal breath control," Dylan explains in his wonderfully insane liner notes. "The subject matter — tho meaningless as it is — has something to do with the beautiful strangers." And that's what the nine songs on Highway 61 add up to: a late-night road trip through an America full of beautiful strangers who'll never get back home.

Highway 61 is the middle album in the trilogy of Bringing It All Back Home and Blonde on Blonde—from that moment when Dylan flipped for the Beatles, went electric and banged out these three rock & roll albums in the space of 14 manic months, three albums everybody (including Dylan) has been trying to live up to (or just plain imitate) ever since. All three have different flavors — if Bringing It All Back Home takes off from the Beatles, Highway 61 is the Stones and Blonde on Blonde is Smokey Robinson — but unlike the other two, Highway 61 never lets up. This album has no "On the Road Again" or "Obviously Five Believers" — a moment of pleasant filler where you can catch your breath. Each of the nine songs tells its own immaculately frightful story.

And more than Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 is a band album, rather than a solo album. The songs are juiced with perfect moments of musical interaction — Charlie McCoy's guitar on "Desolation Row," Paul Griffin's piano on "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," Bobby Gregg's drums on "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry," Michael Bloomfield's twang in "Tombstone Blues," everybody and everything on "Ballad of a Thin Man." Even the infamously out-of-tune guitar on "Queen Jane Approximately" adds to the spirit.

I first heard "Like a Rolling Stone" on the radio as a little kid in the Seventies, on a short-lived Boston Top 40 AM station called WACQ — the voice so threatening, so disturbing, sneering like the Fonz, except also a cool voice that would make anyone itch to join the wild adventure he was singing about. He did that trademark Dylan move of changing his mind about the lyrics in the middle of a word — "To be haaaa-on your own!" (And to think some people still trust this man's lyric sheets.) How did he get away with that? It was a voice like nothing else I'd ever heard. Then the DJ segued right from "Like a Rolling Stone" to the disco hit "Heaven on the Seventh Floor," about getting stuck in an elevator with a foxy lady. Hard to believe that station went out of business.

I spent so much of my teen years trying to decipher those liner notes and that Daniel Kramer cover photo. Dylan stares out at the camera in Jewish-cowboy mode, Paul Newman–style, with mystery-tramp eyes that seem to ask, "Do you want to make a deal?" Behind him, a girl in a Creamsicle-striped T-shirt stands with her camera, impatiently waiting for him to take her out for a ride. (The girl was actually a boy — Dylan pal Bob Neuwirth, whose gender-neutral crotch adds a lot to the cover's power.) The photo captures the restless let's-gooo vibe at the start of a road trip, a vibe that lasts about halfway through the first verse of "Like a Rolling Stone," which is where the trip gets weird. You can still feel Dylan's eyes on you through the album, his head tilted at that curious angle — what, you thought this ride was going to be fun or something?

Somehow, with so much poetic imagery on one album, the most haunting line is one of the simplest — that moment in "It Takes a Lot to Laugh" when Dylan drawls, "I been up all night, leaning on the windowsill." The whole album is a windowsill the world has been leaning on for 50 years — these songs are magnificently bleak company for staying up and brooding all night. And listening to Highway 61 now, it's hard to believe the guy who sings these songs has gotten a night's sleep since.

It's an album that begins with a warning to pawn your diamond ring and save your dimes and keep track of all the people you fucked over yesterday, because they're the same people you'll be begging for hand-outs tomorrow. But it's also an album that ends with a man signing off a letter telling you that he's seen too much depravity in the city to read any more of your letters from home. ("When you asked how I was doing, was that some kind of joke?") The album begins by laughing at a stuck-up young kid who never thought she'd wind up on Desolation Row; it ends with a no-longer-young kid who's given up hope he'll ever get out. The album begins by mourning all the two-bit friends you met in the big city who ripped you off for drugs and sex and money, the "beautiful strangers" who turned out to be Not Your Friends; the album ends by cheerfully promising that you can't go back home to your old friends or family either.

But all the wintertime-is-coming nightmares on this album coexist with Dylan's wildest, most generous comedy. It's the most compassionate album he ever made, because it's the album where he finds every American he meets hilarious. There isn't any moral condemnation, which must be unique for a Sixties Dylan album — even his enemies, the lepers and crooks promoting our next world war, crack him up. His empathy for Queen Jane's midlife blues must have been shocking in 1965, as if it isn't now; he takes her side against her resentful children. Queen Jane and Mr. Jones could be Miss Lonely's parents. (Or Queen Jane might be the badass Second Mother who runs off with the Seventh Son.)

People might have heard "Ballad of a Thin Man" as a denunciation of Mr. Jones, but Dylan is singing too deeply for that — the ghostly "whooooa-oooow" he lets out at the end isn't the kind of sound you make in a song about somebody else's problems. Dylan feels Mr. Jones because every local loser on this highway — every American — has a little of Mr. Jones' confusion in them. And none of them really knows what's happening, although it's a tribute to Dylan's genius that his voice still makes you suspect he's got the secret tucked away in his boot.

If there's one song that's grown the most over the years, it's "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," where Dylan strikes an impossibly friendly tone even as he sings about total devastation, stuck on the long road between Juarez and New York City (2,178 miles!), where it's just one loser after another. Dylan vows to head back to where he came from, even though he knows the NYC he left won't be there anymore. It's a sad song that nonetheless makes you smile wherever you encounter it — sampled brilliantly by the Beastie Boys on Check Your Head, or banged out by the Grateful Dead, with Phil Lesh mangling the lyrics from "my best friend the drummer won't even tell me what it is I dropped" to "I started out on Heineken but soon hit the harder stuff."

I saw Dylan do "Tom Thumb's Blues" at Madison Square Garden in November, 2001, right after 9/11, and the opening notes set off frenzied waves of joy throughout the crowd ("He's doing that one! The 'going back to New York City' one!"), even though every character in the song is truly and utterly fucked. Dylan almost halfway cracked a smile as 20,000 people sang the punchline back at him. That wiseass compassion is why so many listeners keep hearing themselves in these songs. Even with all the danger and turmoil Dylan finds on this highway, the tears on his cheeks are from laughter.

(Pour voir la version originale, avec les pubs, c'est ici : http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/happy-birthday-highway-61-dylans-weirdest-funniest-album-turns-50-20150827 ) | |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 1 Déc - 22:29 Mar 1 Déc - 22:29 | |

| Ah très bien. Je vais regarder ça. Ça fait un bout de temps que je ne trouve plus de presse anglophone dans la banlieue et la campagne (si, là on trouve la presse tabloid ou people) où je séjourne. | |

|   | | used_spoon

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2167

Age : 33

Date d'inscription : 19/12/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mar 17 Mai - 15:27 Mar 17 Mai - 15:27 | |

| http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/mavis-staples-on-summer-tour-with-bob-dylan-its-really-an-honor-20160509

Interview de Mavis Staples sur la tournée US de cette été.

Plein d'anecdotes intéressantes sur leur relation. | |

|   | | Jack Fate

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 1010

Age : 43

Date d'inscription : 21/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mer 18 Mai - 23:09 Mer 18 Mai - 23:09 | |

| - used_spoon a écrit:

- http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/mavis-staples-on-summer-tour-with-bob-dylan-its-really-an-honor-20160509

Interview de Mavis Staples sur la tournée US de cette été.

Plein d'anecdotes intéressantes sur leur relation. J'adore ce passage! You're playing so many amazing venues, like the Greek Theater and the Santa Barbara Bowl. Yeah. It's gonna be fun. I might ask him, "Bobby, if we get into one of these hotels that has a kitchenette, would you want me to cook for you?" What meal would you cook for him? Bobby is probably a vegetarian by now. I just don't know. I'd tell him to make up the menu, whatever he wants; that's what would I would fix for him. He might want kale! Je ne sais pas si vous avez eu l'occasion de voir le documentaire que HBO lui a consacré (et dans lequel Dylan intervient), mais ça a vraiment l'air d'être une femme adorable. En lisant cette interview, on se rend compte qu'elle apprécie bien plus Robert Zimmerman que de Bob Dylan. C'est certainement une des choses qui doit plaire à Bob. Une biographie que j'avais lu indiquait d'ailleurs que Dylan se sentait particulièrement bien entouré d'afro américains parce qu'ils étaient dans l'ensemble moins "fan" de sa musique que les blancs qui tendaient à lui vouer un culte. Il parait qu'il adore (ait?) la nourriture afro américaine aussi. Dans tous les cas, la tournée Staples / Dylan m'enthousiasme bien plus que le concert Dylan / Rolling Stones. Quand même, refuser d'écouter un album de Dylan avant qu'il ne sorte et alors qu'il te supplie de venir parce qu'il est une heure du matin, il faut le faire  | |

|   | | used_spoon

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2167

Age : 33

Date d'inscription : 19/12/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 23 Mai - 12:50 Lun 23 Mai - 12:50 | |

| http://pitchfork.com/thepitch/1157-beyond-the-bootlegs-bob-dylans-unreleased-holy-grails/?mbid=social_facebook

The Lost Eighties Sessions with Al Kooper, T-Bone Burnett, and Cesar Rosas

The mid-1980s were a low point for Dylan as a record-maker, with two half-hearted LPs, Down in the Groove and Knocked Out Loaded, suffering from the most scathing (or just plain indifferent) reviews of Dylan’s career. But Rolling Stone's Mikal Gilmore was present for studio sessions showing that Dylan could still find inspiration if the circumstances were right. With a motley crew of session musicians including Al Kooper, T-Bone Burnett, Los Lobos guitarist Cesar Rosas, R&B saxophonist Steve Douglas, and bassist James Jamerson Jr., Gilmore writes that Dylan cut well over 20 songs ranging “gritty R&B, Chicago-steeped blues, rambunctious gospel, and raw-toned hillbilly forms.” And not a single one has seen the light of day, on bootleg or otherwise.

On a encore de quoi être gaté niveau bootlegs ! | |

|   | | hazel

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 4717

Age : 33

Localisation : Rennes

Date d'inscription : 16/01/2010

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Sam 2 Juil - 12:05 Sam 2 Juil - 12:05 | |

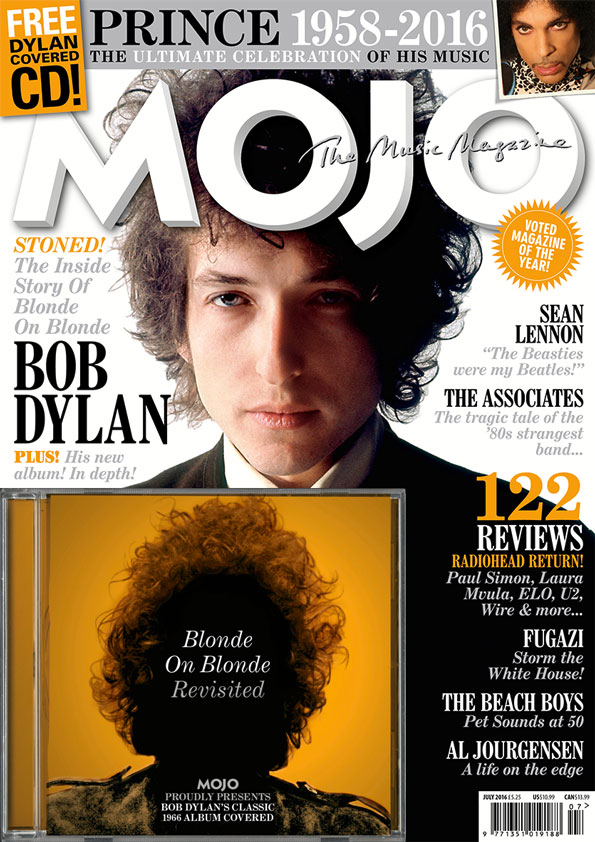

| J'ai acheté le MOJO spécial Dylan et le dossier est passionnant ! La presse française fait de la peine en comparaison. De belles photos, des intervenants de luxe et des choses inédites sur "Blonde On Blonde" sur lequel je pensais avoir tout lu. En bonus, un CD de reprise de l'album avec Kevin Morby qui signe un magnifique "Temporary Like Achilles". Parfait !  _________________  | |

|   | | used_spoon

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2167

Age : 33

Date d'inscription : 19/12/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 4 Juil - 11:49 Lun 4 Juil - 11:49 | |

| Oh, tu pourrais nous uploader le CD quelque part?  | |

|   | | Jack Fate

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 1010

Age : 43

Date d'inscription : 21/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Mer 7 Sep - 22:08 Mer 7 Sep - 22:08 | |

| à ce niveau, c'est même plus la peine de chercher à comprendre

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/08/arts/music/bob-dylan-iron-archway-casino.html | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Sam 10 Sep - 12:45 Sam 10 Sep - 12:45 | |

| Sympa, il s'amuse bien le vieux. Quel artiste ! | |

|   | | Chinaski

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 444

Localisation : Trans City

Date d'inscription : 14/07/2006

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Sam 17 Sep - 20:42 Sam 17 Sep - 20:42 | |

| - Jack Fate a écrit:

- à ce niveau, c'est même plus la peine de chercher à comprendre

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/08/arts/music/bob-dylan-iron-archway-casino.html ce vieux est fabuleux. je veux mourir le même jour que lui | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Dim 23 Oct - 14:22 Dim 23 Oct - 14:22 | |

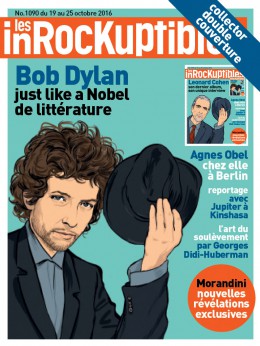

|  Double couverture des inrocks cette semaine, Dylan/ Cohen. Deux actualités brûlantes, deux poètes. 6 pages seulement sur le Nobel de Bob mais 2 articles sympas dont un papier signé Silvain Vanot | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Dim 23 Oct - 14:41 Dim 23 Oct - 14:41 | |

| est on a ça aussi sur le web, toujours dans les inrocks:

http://www.lesinrocks.com/2016/10/23/cinema/mille-visages-de-bob-dylan-a-lecran-11873708/

Dylan et le cinéma ... manquerait plus qu'il est un césar du meilleur acteur ! | |

|   | | JeffreyLeePierre

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2899

Age : 57

Localisation : Paris

Date d'inscription : 06/01/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Dim 30 Oct - 1:30 Dim 30 Oct - 1:30 | |

| Un numéro hors séries Inrocks2 à l'occasion du Nobel.  Pas encore lu, juste parcouru : vu de loin, ça ressemble à une compilation d'articles passés des Inrocks. | |

|   | | gengis_khan

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2928

Age : 34

Localisation : Alpes

Date d'inscription : 25/07/2012

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 31 Oct - 15:35 Lun 31 Oct - 15:35 | |

| http://bibliobs.nouvelobs.com/actualites/20161026.OBS0354/20-choses-a-savoir-sur-bob-dylan-prix-nobel-du-trapezisme.html 21 choses à savoir sur Bob. Pourquoi 21...? ba pourquoi pas... en fait dans l'ensemble c'est plutôt anecdotique. Cependant j'ai découvert cette citation de Jimi Hendrix: « La première fois que j'ai entendu Dylan, je me suis dit: “Ce type est admirable, il faut avoir du cran pour oser chanter aussi faux.” Et puis je me suis mis à écouter les paroles. Ça m'a conquis.»Il lui aurait certainement décerné le Nobel déjà en 1967 quand il a découvert All Along the Watchtower Le 15ème point, "passoire" est amusant, à propos de Self Portrait, je vous laisse le découvrir !  | |

|   | | Baptiste

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 2570

Date d'inscription : 19/12/2006

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Ven 2 Déc - 15:08 Ven 2 Déc - 15:08 | |

| - JeffreyLeePierre a écrit:

- Un numéro hors séries Inrocks2 à l'occasion du Nobel.

Pas encore lu, juste parcouru : vu de loin, ça ressemble à une compilation d'articles passés des Inrocks. J'ai l'impression qu'il s'agit de la réédition d'un HS précédent. Comme "Le Monde", d'ailleurs, qui a recyclé un magazine qu'ils avaient sorti il y a quelques années.

_________________

Sing along Bob

Sing, sing along Zimmerman

J'suis cow-boy à Paname

Mais c'est la faute à Dylan

| |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Lun 19 Déc - 2:14 Lun 19 Déc - 2:14 | |

| Dylan et le blues

ISSUE 95, WINTER 2016

Oxford American (magazine)

“Think Twice”

By Elijah Wald

December 13, 2016

I’ve spent a lot of time recently listening to Bob Dylan’s second album. Not Freewheelin’, the LP with him and Suze Rotolo on the cover and “Blowin’ in the Wind” in the grooves. That’s the one we know, because a couple of songs off it were picked up by the Chad Mitchell Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary—and then by everyone from Bobby Darin to Marlene Dietrich—and Dylan was hailed as a poet and the voice of a generation. But before that happened, he’d spent a year working on a follow-up to his first LP that displayed very different skills and inclinations.

My second Dylan album is the one with a loping piano version of Robert Johnson’s “Milkcow’s Calf Blues,” punctuated with wild falsetto whoops. The one with a propulsive “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” fresh in his mind after his recent session playing harmonica for Big Joe Williams. The one with “Wichita,” tracing his mythical hobo travels:

When I left Wichita, the weather was killing me . . .

I landed in West Memphis, I sure did not have a dime . . .

I’m going down to Louisiana, mama, where that green river run

You can run and tell my mother, my rambling has just begun.

That record was never commercially released, but the studio tracks have survived and been traded among hardcore fans, and they show an alternate Dylan: not the folky bard of the standard biographies, but the hippest young blues singer in Greenwich Village.

For fifty years, we’ve been told that Dylan arrived in New York singing Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl ballads, began writing his own protest songs in Guthrie’s style, then grafted that style with the modernist poetics of the French Symbolists and the American Beats. That story made perfect sense to all of us who discovered Dylan after Freewheelin’ and The Times They Are A-Changin’—which is to say, almost everyone outside a small band of early fans in the Village. But to a great extent it is revisionist history, ignoring the way his first album was presented and how those fans described him before the folk-poet thing took off.

Take his first newspaper review: in September 1961, Dylan played two weeks at Gerde’s Folk City with the Greenbriar Boys, and Robert Shelton gave him a rave in the New York Times. A quarter century later, Shelton would recall that Dylan sang in a “rusty voice, suggesting Guthrie’s old recordings,” with an overlay of Dave Van Ronk and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. But back in 1961 Shelton didn’t mention Guthrie; he wrote that Dylan’s voice had “the rude beauty of a Southern field hand musing in melody on his porch. . . . He may mumble the text of ‘House of the Rising Sun’ in a scarcely understandable growl or sob, or clearly enunciate the poetic poignancy of a Blind Lemon Jefferson blues.”

When Dylan’s eponymous first album appeared, in March of 1962, the liner notes—again by Shelton, using the pseudonym Stacey Williams—described him as “a young Woody Guthrie” but immediately followed with “or a composite of some of the best country blues singers.” That portrayal was fleshed out with mentions of Sonny Terry and Little Walter Jacobs as Dylan’s harmonica models, his week at Folk City opening for John Lee Hooker, a meeting with Mance Lipscomb, and his debt to the recordings of Big Joe Williams and Rabbit Brown, along with Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Jelly Roll Morton, Carl Perkins, and early Elvis Presley. (Individual song notes added Jesse Fuller, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Roy Acuff, and the Everly Brothers.) A Village Voice reviewer praised that album’s comic “Talkin’ New York,” but ignored Dylan’s only other composition, the nostalgic “Song to Woody.” Instead, the writer hailed him as a powerful musician and performer, “a growling, grumbling force backed up by flailing guitar which can drive you wild,” and called the disc an “explosive country-blues debut.”

That review startled me when I first read it a couple of years ago, because I had always heard Dylan’s early style described in very different terms. By 1963, Shelton was setting a pattern that has been followed ever since, writing: “His voice is small and homely, rough but ready to serve the purpose of displaying his songs.” And yet, in retrospect, the Voice’s description seems uncannily prescient, foreshadowing the Dylan who electrified Newport with the Butterfield Blues Band in 1965 and cut Highway 61 Revisited—or the Dylan on 2001’s Love and Theft and at his best shows today.

I missed the continuity between Dylan’s early blues and his later rock excursions because, like almost everyone in the 1960s, I became aware of him through other performers: as the composer of Peter, Paul and Mary’s lilting protest anthems, the Guthriesque ballads Pete Seeger performed at Carnegie Hall, and the Byrds’ mellow take on “Mr. Tambourine Man.” By the time I discovered his own, rawer versions of the songs, I associated him with those performers and continued to see him through that prism: as a brilliant, difficult artist whose work was a gritty cousin to the pretty pop-folk style.

In terms of broad cultural impact, it makes sense to see Dylan primarily as a groundbreaking lyricist, a modern bard who has inspired generations of singer-songwriters. That is the Dylan who just won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and whose influence permeates every strain of popular music. But the focus on Dylan’s writing makes it easy to forget that he was signed by Columbia Records and hailed by early reviewers as a compelling musician and singer, and as a rough blues artist rather than a sensitive balladeer. When he went electric it was a return to form, and the title of his breakthrough hit, “Like a Rolling Stone,” neatly signaled his kinship with those other young blues fans who were tearing up the charts that year—not coincidentally with a series of Dylan pastiches: “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” followed by “Get Off of My Cloud” and “19th Nervous Breakdown.” (The British r&b scene had embraced Dylan as a blues artist from the start, the Animals copping “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” and “House of the Rising Sun” off his first LP.)

By 1963, it made sense to market Dylan as a folk poet. But before adopting that strategy Columbia actually tried the electric route: Dylan’s first single, released on the cusp of that year, was “Mixed-Up Confusion,” a rockabilly raver recorded alongside a hot take of Big Boy Crudup’s “That’s All Right” (with Bruce Langhorne playing the same guitar riff he later used on “Maggie’s Farm”) and a souped-up rewrite of an old section-gang song, “Rocks and Gravel.” The single went nowhere, but it is easy to see why Columbia gave it a shot: Dylan didn’t sound like a smooth-voiced pop-folky, and proudly affirmed his roots in rock & roll. His rambling hobo stories included claims of backing Gene Vincent and Bobby Vee, and the references to Presley, Perkins, and the Everlys on his first album were backed up by the “Wake Up, Little Susie” riff he tacked on to Tommy McClennan’s “New Highway No. 51.”

Many of Dylan’s friends and mentors on the folk scene dismissed rock & roll as commercial pap, but he saw it in different terms. As a Minnesota teenager he had discovered Gatemouth Page’s nighttime r&b broadcasts from the wilds of Louisiana, and a high school pal taped him playing high-powered piano and arguing that Elvis was just imitating Little Richard and Clyde McPhatter. As his tastes expanded over the next few years, he always maintained a deep affinity with black music. That was one of the things that attracted John Hammond, the white producer who brought him to Columbia, and Tom Wilson, the black jazz connoisseur who replaced Hammond toward the end of the Freewheelin’ sessions. Wilson said he had never cared for folksingers, but Dylan reminded him of Ray Charles—especially the blues work, which was “raw, different from other whites, original.”

To my ears, Dylan’s first album sounds more raw than original, but the blues tracks he cut over the next year show a growing ability to twist familiar lyrics and improvise quirky variations. Unlike most white revivalists, who tended to repeat whatever verses Robert Johnson or Lemon Jefferson sang on a treasured 78, he treated blues as a living, changing tradition. In part, that was because he had direct connections to older artists: Suze Rotolo recalled him spending hours hanging out in John Lee Hooker’s hotel room, and other friends were struck by his close relationship with Big Joe Williams (although biographers are universally dubious, both claimed they’d met when Bob was a kid).

Williams and Hooker were masters of a tradition that took individual songs as points of departure, reworking old verses and improvising new ones to fit the moment and the mood. Dylan absorbed that lesson, taking favorite recordings as models rather than texts. In his memoir, Chronicles, he recalls Hammond giving him an advance acetate of Robert Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers. That album has been the source of innumerable covers in the ensuing decades, most by sincere acolytes recycling Johnson’s phrases and mimicking his guitar licks. But Dylan describes a different process:

I copied Johnson’s words down on scraps of paper so I could more closely examine the lyrics and patterns, the construction of his old-style lines and the free association that he used, the sparkling allegories, big-ass truths wrapped in the hard shell of nonsensical abstraction . . .

Which is to say: the poetic Dylan wasn’t always chasing Rimbauds. (An awful pun, stolen from Dorothy Parker—but that’s part of the tradition, too. Witness Johnson: “A woman is like a dresser, some man’s always rambling through its drawers.”) Even his most abstract songwriting was deeply informed by his immersion in blues. When he got his first publishing contract, with Leeds music, the initial batch of demos included Guthriesque ballads, but also a rewrite of Johnson’s “Crossroads Blues” called “Standing on the Highway” and an extension of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning” titled “Poor Boy Blues,” in which he followed three of Wolf’s verses with a heartfelt moan well-suited to the baby-faced kid from Hibbing: “Hey, mister bartender, I swear I’m not too young . . .” He was recording for copyright men who wanted marketable product, but it sounds like he’s making up lines as he goes and would have sung something completely different on another day.

That’s the special excitement of Dylan’s blues work—the sense that every performance was being captured in the moment. The songs that happened to get preserved at any session were just a sample of what he was doing that week, and if he’d recorded a day earlier or later he would have done different ones, or the same ones in different ways. When he cut Johnson’s “Milkcow’s Calf,” he played piano on the first take, then switched to guitar for the second. At a live show a few months later, he was using his “Milk Cow” yodel for a Kokomo Arnold pastiche and singing Johnson’s “Ramblin’ on My Mind.” At a gig a few months after that, he sang Johnson’s “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” with a mix of old and adapted verses. We’ll never know what he sang on the nights that didn’t happen to get taped, or how he sang, just as we don’t know what Johnson himself sang thirty years earlier on all his unrecorded nights in bars and juke joints from San Antonio to New York City.

Listening to my imagined Dylan Blues album, I hear the flaws as well as the brilliance, and can’t argue with the choice to hold it back in favor of Freewheelin’ in 1963. But I still keep hoping it will be released, if only to complicate the familiar narrative of rock history. That narrative typically pairs Dylan with the Beatles in a pantheon of cultural revolutionaries who transformed rowdy teen dance music into a mature, intelligent art form. Blues comes into that story as a source of soul, guts, and drive, traced through Robert Johnson and Little Richard to the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix. But the mature intelligence comes from elsewhere: the Beat poets, the French Symbolists, the literary traditions of Shakespeare and “Barbara Allen.” Dylan is the matchmaker who married folk ballads to Verlaine and Rimbaud, then shocked his early fans by backing those heady lyrics with a Beatle beat.

I’m switching out that narrative for another, in which Dylan was recording solid blues in 1962, experimenting with electric band tracks and the sparkling allegories of the Delta masters, and continued those explorations a couple of years later on Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61. The British Invasion opened a commercial door, but that music—the music of John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters, of Big Joe Williams, Mance Lipscomb, and Robert Johnson—didn’t need any lessons in maturity and intelligence from twenty-year-old rockers, Beat poets, or French Symbolists.

For half a century, as his literary gifts were analyzed ad infinitum and he was crowned with a bushy effusion of academic laurels, Dylan has continued to explore the blues tradition, growing occasionally beyond it but more frequently within it. The Nobel committee places him in the tradition of Homer and Sappho, but I prefer to think of him as a blues singer—and assume he would be the first to recognize that as at least an equal honor.

Elijah Wald

Elijah Wald is a musician, writer, and sometime academic whose books include Escaping the Delta, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n Roll, and Dylan Goes Electric! | |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: New York Times 20170324 Sujet: New York Times 20170324  Sam 1 Avr - 0:04 Sam 1 Avr - 0:04 | |

| https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/24/books/review/after-dylans-nobel-what-makes-a-poet-a-poet.html?_r=1 | |

|   | | Monsieur Plume

People Get Ready!

Nombre de messages : 82

Localisation : Poitou-Charentes

Date d'inscription : 25/10/2011

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Sam 1 Avr - 0:09 Sam 1 Avr - 0:09 | |

| Allez hop je le mets in extenso.

After Dylan’s Nobel, What Makes a Poet a Poet?

By DAVID ORRMARCH 24, 2017

“I’m a poet, and I know it. Hope I don’t blow it.”

The Swedish Academy is responsible for awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature, and over the past hundred years the group has become renowned for such feats of discernment as denying the prize to Robert Frost, perhaps the most widely read poet of the 20th century, and bestowing the award upon the Swedish writer Erik Axel Karlfeldt, perhaps the most widely read poet in the Karlfeldt family. As has been extensively discussed, the academy’s most recent attempt at literary kingmaking was to deliver the Nobel to Bob Dylan, perhaps the most widely read poet whose work is not, by and large, actually read.

Months after his elevation, the response to Dylan’s prize — and in particular to what it might suggest about the words “literature” and “poetry” — remains mixed. Various Dylan fans continue to be pleased, various English-language novelists continue to be annoyed, and various American poets continue to say something or other that no one is paying much attention to. Beneath the surface of this amusing situation, however, is an intriguing tangle of questions about high and low culture, the nature of poetry, the nature of songwriting, the power of celebrity and the relative authority of different art forms. These questions all largely turn on the notion that Bob Dylan is, if not a poet, at least poet-ish to some notable degree. Indeed, “he is a great poet in the grand English tradition,” according to Sara Danius, the permanent secretary of the academy. It’s a theory every poetry critic is familiar with, if only because it often emerges in conversations with the many people who don’t read poetry. “I don’t know much about the things you write about,” one’s airplane seat companion will declare, “but I listen to [insert famous musician] and to me, he/she is a real poet.”

And why not? Lyrics look like poems, or at least a particular kind of poem. They often rhyme. And when we hear the words in a well-delivered song, the experience we have seems to resemble the way we’re often told poems are supposed to feel — like a distillation of overwhelming emotion. Plus, as the academy is quick to note, the ancient Greeks didn’t distinguish between poetry and song. “In a distant past,” Dylan’s citation reads, “all poetry was sung or tunefully recited, poets were rhapsodes, bards, troubadours; ‘lyrics’ comes from ‘lyre.’ ” Given all these points in favor, isn’t it better to expand a word’s definition — “literature” or “poetry” in this case — than to limit it?

Maybe. And yet this line of argument becomes increasingly problematic the further it proceeds. Yes, song lyrics look like poems if you print them on a page. But they’re very rarely printed on a page, at least for the purpose of being read as poems. Mostly they’re printed so that people can figure out what Eddie Vedder is saying in “Yellow Ledbetter.” And for that matter, screenplays and theatrical plays resemble each other more closely than do songs and poems, but that has yet to result in Quentin Tarantino winning the Pulitzer in drama. As for the ancient Greeks, well, the fact that a group of people thought about something a certain way nearly three millenniums ago doesn’t seem like a compelling argument for thinking the same way today. (The ancient Greeks also sacrificed animals to their gods — maybe the Swedish Academy should dispatch a few reindeer, and see if that produces a laureate willing to show up for the ceremony next time around?)

Then there is the music. A well-written song isn’t just a poem with a bunch of notes attached; it’s a unity of verbal and musical elements. In some ways, this makes a lyricist’s job potentially easier than a poet’s, because an attractive tune can rescue even the laziest phrasing. But in other ways, the presence of music makes songwriting harder, because the writer must contend with timbre, rhythm, melody and so forth, each of which presents different constraints on word selection and placement. To pick just one example, lyricists must account for various forms of musical stress beyond the relatively straightforward challenge of poetic meter. In Fleetwood Mac’s otherwise poignant “Dreams,” Stevie Nicks tells us, “When the rain washes you clean, you’ll know,” a line that would be completely fine in a poem. Yet because the second syllable of “washes” falls at a higher pitch and in a position of rhythmic emphasis with respect to the first syllable, Nicks is forced to sing the word as “waSHES.” This kind of mismatch is common in questionable lyric writing; another example occurs at the beginning of Lou Gramm’s “Midnight Blue,” in which Gramm announces that he has no “REE-grets” (all of them presumably having been eaten by his egrets).

Beyond the many technical differences, though, there is the simple fact that people don’t really think of songs as being poems, or of songwriters as being poets. No one plays an album by Chris Stapleton, or downloads the cast recording of “Hamilton,” or stands in line for a Taylor Swift concert, and says something like, “I can’t wait to listen to these poems!” That’s true no matter how skillful the songs, since competence isn’t how we determine whether a person is participating in a particular activity. We don’t say someone isn’t playing tennis just because she plays less brilliantly than Serena Williams, nor do we say William McGonagall wasn’t a poet just because his poems were terrible. So if Bob Dylan is a poet, it follows that anyone who does basically the same thing that Dylan does should be considered a poet as well. Yet while people routinely describe both Dylan and Kid Rock as “songwriters” and “musicians,” there are very, very few people who refer to Kid Rock as a poet.

That’s because when the word “poetry” is applied to Dylan, it isn’t being used to describe an activity but to bestow an honorific — he gets to be called a poet just as he gets to be a Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient. This may seem odd, because we don’t typically recognize excellence at one endeavor by labeling it as another, different venture. But poetry has an unusually large and ungrounded metaphoric scope. Most activities exist as both an undertaking (“hammering,” as in hitting something with a hammer) and a potential metaphor tied to the nature of the activity in question (“McGregor is hammering his opponent now!”). But poetry’s metaphoric existence is only loosely tethered to its sponsoring enterprise. When a person says something like, “That jump shot was pure poetry,” the word has nothing to do with the actual practice of reading or writing poems. Rather, the usage implies sublimity, fluidity and technical perfection — you can call anything from a blancmange to a shovel pass “poetry,” and people will get what you’re saying. This isn’t true of opera or badminton or morris dancing, and it can cause confusion about where metaphor ends and reality begins when we talk about “poetry” and “poets.”

Moreover, while most people have limited experience with poems, they do generally have ideas about what a poet should be like. Typically, this involves a figure who resembles — well, Bob Dylan: a countercultural, bookish wanderer who does something involving words, and who is eloquent yet mysterious, wise yet innocent, charismatic yet elusive (and also, perhaps not coincidentally, a white dude). When you join all of these factors — the wide metaphoric scope of “poetry,” the lack of familiarity with actual poetry or poets, the role-playing involved in the popular conception of the poet — it’s not hard to see how you might get a Nobel laureate in literature who doesn’t actually write poems.

Yet if this dynamic explains why people weren’t baffled by Dylan’s Nobel, it doesn’t explain why quite a few poets and English professors wanted him anointed. One would think, after all, poets might be put off by the idea that songwriters can be poet enough to win a prize in literature, when the implied relationship is so clearly a one-way street. (John Ashbery will be waiting a long time for his Grammy.) But in fact, poets have often benefited from the blurred edge of their discipline. Poetry has one primary asset: It’s the only genre automatically considered literary regardless of its quality. Popular songwriting, by contrast, has money, fame and Beyoncé. So there is an implicit trade going on when, for example, Donald Hall includes the lyrics to five Beatles songs in his anthology “The Pleasures of Poetry” (1971). But it isn’t just a straight swap in which song lyrics are granted literariness and poems take on a candle flicker of celebrity. Poetry also benefits in a subtler and more important way, because the implicit suggestion of these inclusions is that only the very best songwriters get to share space with poets. Poetry’s piggy bank may remain empty, but its cultural status is enhanced — in a way that is hugely flattering to poets and teachers of poetry, even as it is insulting to brilliant songwriters who happen to be less famous than, say, the Beatles.

Which is what makes this a risky game for poets. Culture is less a series of peaceable, adjacent neighborhoods, each inhabited by different art forms, than a jungle in which various animals claim whatever territory is there for the taking. It’s possible that poets can trail along foxlike behind the massive tiger of popular music, occasionally plucking a few choice hairs from its coat both to demonstrate their superiority and to make themselves look a bit tigerish. With Dylan’s Nobel, we saw what happens when the big cat turns around.

David Orr has been writing the On Poetry column for the Book Review since 2005. His new book, “You, Too, Could Write a Poem,” was published last month.

A version of this article appears in print on March 26, 2017, on Page BR22 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: The Lyrics Laureate. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe | |

|   | | Chinaski

This Land Is Your Land

Nombre de messages : 444

Localisation : Trans City

Date d'inscription : 14/07/2006

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  Jeu 20 Avr - 18:28 Jeu 20 Avr - 18:28 | |

| http://www.telerama.fr/musique/coffret-dylan-66-deux-mois-d-ecoute-une-folie-de-fan,156982.php | |

|   | | Contenu sponsorisé

|  Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse Sujet: Re: Dylan dans la presse  | |

| |

|   | | | | Dylan dans la presse |  |

|

Sujets similaires |  |

|

| | Permission de ce forum: | Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum

| |

| |

| |